“Hmmm,” the staffer said, wearing the smile of a customer service worker. “We don’t have that apple, but we might have the tree in our fruit tree section. I can check.”

“But I want the apples. What will I do with the tree?”

“You don’t have a yard? Many customers taste the apples in order to decide which to grow in their yard.”

“I do have a yard, but I don’t have time to care for a tree.”

“I’m sorry. I can’t help you, then.”

“Wait. Speaking of yards. There’s something else. Advice. I need an expert to tell me whether plums on a broken branch will ripen.”

“But… it’s not plum season.”

“I know, this is from last spring. My neighbor’s plum tree—a branch hangs over my yard. But the branch is broken.”

“Okay.”

“It’s going to happen again. Here, I have the photo. Are you an expert? If not, please, get one for me.”

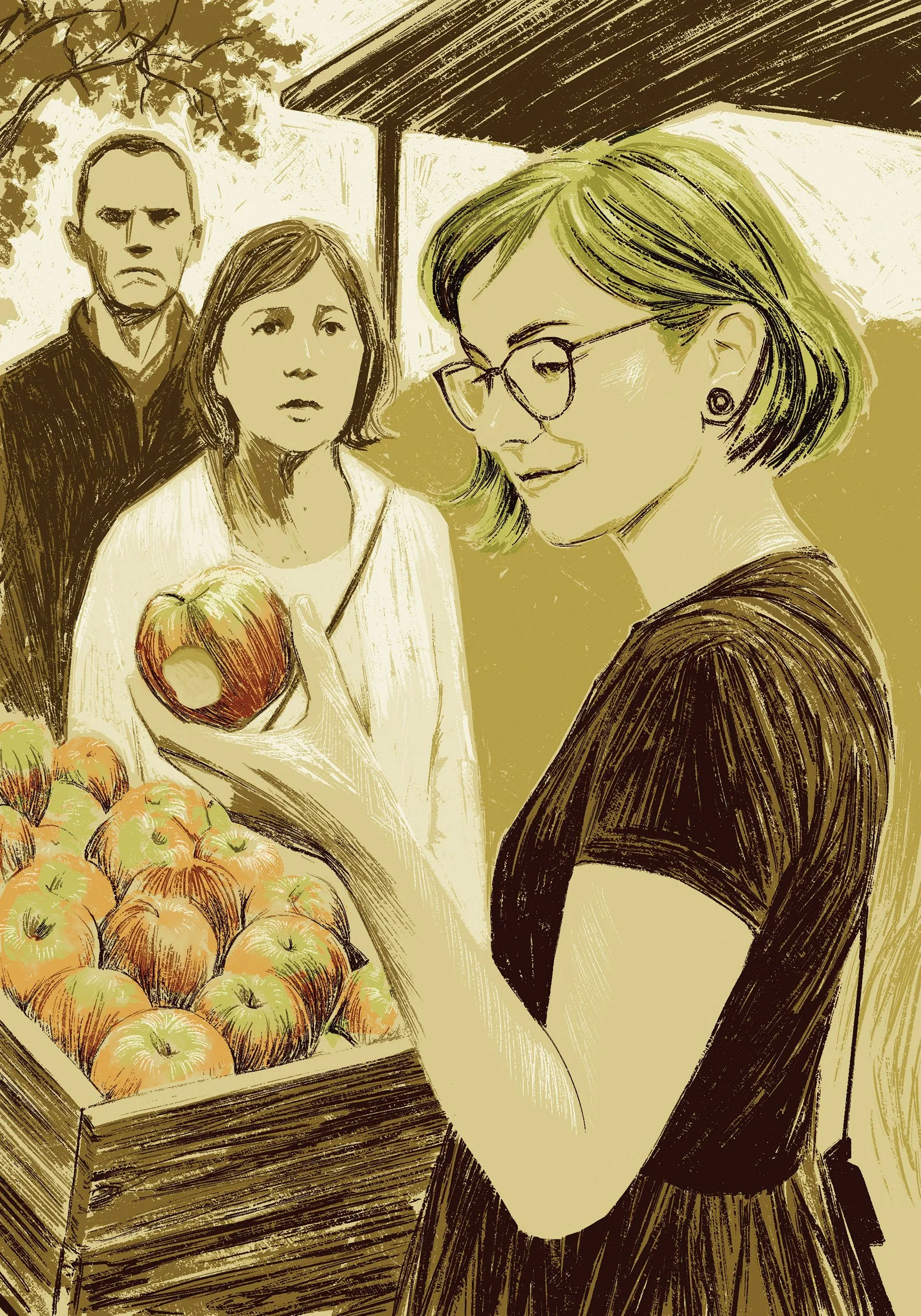

I tried to inspect the apples and look like I wasn’t listening. Her voice had taken on a tone I didn’t care for. She rummaged in her tote, pulled out her phone, and began to scroll through the photographs on it, as the staffer waited, looking around at the growing crowd. The staffer sighed a small sigh and said, “It’s busy, but if you find it, I am happy to take a look.”

• • • •

“I want a referral to an expert.” She held the phone out and pointed, insisting. “I need to discuss the best course of action. It’s clear to me that the proper course is to prune off the heavy broken branch. Here, see here, where it’s broken?”

“Mmmmhmmm.”

“It’s weighing down the tree and sagging over my yard.”

“This is your neighbor’s tree, right? That could be one way of approaching it, but it’s really up to them.”

“But the plums, will they ripen?”

“Unfortunately, probably not.”

“You don’t sound certain. I’d like an expert.”

“The plums will not ripen. I was trying to be kind.”

“Well, then. Do you have a recipe?”

“A recipe?”

I stood, dazed or transfixed. I could not tear my eyes from the scene unfolding before me. Ordinarily, I’d have rolled my eyes and gotten as far away as possible. But this was my daughter.

“For green plums,” she explained. “Since you’re so sure these won’t ripen.”

“Well, you could, um, pickle them.”

“Pickle them?”

“Maybe Asian style? Japanese? Fermentation?”

“No.”

“Well, maybe a soup? To add a little sourness to the broth?

“No.”

“No?”

“No. No. No. That won’t do. It’s got to be sweet.”

The staffer turned away. “I’ll get you a referral number for an expert.” As the staffer walked by me, I heard her mutter under her breath, “Heaven have mercy upon us all!”

As soon as the staffer was gone, my daughter walked straight over to the caramel apple table and cut the line. She stood like a small barrel, staring up at the price list. I watched as she ordered the dessert on a stick. I watched as she bit down through the sticky unctuous coating and sank her teeth into the apple’s flesh below.

And I started to feel afraid.

Next to the line, a little girl tugged at her mother’s sleeve, pointed at the apple in my daughter’s hand, said, “I want!”

My daughter smiled down at the girl. “Too late,” she said. “I have eaten it. And now I will eat you too!”

• • • •

I was six when my grandfather caught me with a hand in the literal cookie jar, in his marigold yellow kitchen in a state far from my own. I had been eating the chocolate cookies my grandmother had baked, she said, just for me. “You’re too skinny, hon-ey, I made these cookies for you. I want to spoil you. Eat, eat,” she had said, her hair a halo of soft red curls warming her face. My grandfather looked at me sternly. I started to feel afraid. “Do you really need another cookie?” my grandfather said. “How many of those have you eaten? You’re looking awfully chunky these days. You wouldn’t want to blow up, would you?”

• • • •

I followed her like a helium balloon, bobbing behind her waist. First, she visited the apple cider press, told the workers operating the machine that they were doing it all wrong. Then, she lectured a family, their eyes rolling, on the dangers of raw cider: E. coli and food poisoning that made you want to die.

Next, she wandered into the kids’ activity area where several youngsters were decorating gourds while a genderqueer cowboy was painting other kids’ faces.

“Paint my face,” she said to the cowboy. “I want you to make me a tree. An apple tree. I went through the tasting, and I found the Ashmead’s Kernel to be the best tasting apple. I want you to paint me as that kind of tree.”

What would I ask for? A snake perhaps, cinching its ouroboros around my neck.

“But I don’t know what that kind of tree looks like.”

“Here, I’ll Google it. You can use my phone as a reference.”

“I don’t…”

“That’s what you’re doing here, aren’t you? Making everyone happy?”

The cowboy looked pained. “Do you see this line? The children? I already have a cat and a butterfly and baby Yoda in the queue.”

“Is there a sign that says this is for children only?”

“No, but.”

“I’ll wait my turn,” she said.

• • • •

The only photograph I have of my mother’s mother shows her on a farm with her ten siblings. She wears a dress made from a potato sack and stands between the brother with dwarfism and the sister—oldest, strongest, largest—whose roof she lived under after she left the farm behind.

In the photograph, my grandmother is a child. Seven, maybe. She looks directly into the camera, her hands clenched in fists and her feet planted, wide. In fact, each sibling has the same rooted posture: the men with bow ties and ears that stick out, the women in shirtwaists and buns, even the toddler in the ambiguously-gendered white dress of the era holds its siblings hands and stands on feet like stalks.

I used to wonder what they gave me, all of them, those strangers in my family tree.

I myself had no clan. I was sole sister to my childhood dog. An only, I begged my parents for a sibling, but what they gave me was a labrador. Lucy was truer than true, and sometimes I imagined her paws and my hands were molded from the same primordial clay.

Lucy knew my heart, planted her young body between me and my father’s rage.

Even when my father’s newspaper route didn’t bring home enough food for us to eat, I gave Lucy bits of my meals, Bisquik biscuits or hot dog ends, and she rested her head on my lap and told me I would never be alone.

• • • •

A girl walked by, wheeling a wheelbarrow full of straw. She stared at my daughter and the strange monstrous knots that now covered her painted face.

“What are you supposed to be?” she asked.

My daughter answered: “I am an apple tree, a carnivorous one, and I am going to eat you up.”

The wheelbarrow girl disappeared. In her place, a man with a forklift, and on the forklift, a pumpkin as big as a child. There was nowhere for him to go, my daughter blocking the only open path to the area where I assumed the pumpkin would be displayed.

“Excuse me,” he called, but she didn’t budge. “Excuse me,” he tried again, louder. Finally, he snapped. “If you don’t get out of the way, I’ll drive over you! Fat-ass.” He lurched the forklift in her direction.

My daughter, however, did not flinch. “I have a question for an expert,” she said to the forklift man. “I need an expert to tell me whether the plums on a broken branch will ripen.”

“Lady, get out of my way.”

“Are you an expert? You don’t look like an expert.”

I didn’t want to believe anymore. It was foolish, wasn’t it? I had made her out of hope and suffering, the roots of my ancestry torn out of the ground and replanted. I had made a false family tree and even so, I felt responsible all the same.

I needed to intervene, to protect these people somehow. I stepped to her, put my hand on her arm. “Come with me, please, let me buy you a drink,” I said. “We can talk about the plums,” I said. “I think I know what to do.”

• • • •

So we wandered over to the hard cider tent, showed our IDs, and found a place to lean by the makeshift bar, where barrels were set up to serve as seats. The bartender brought out a basin of cider. She ladled some of the cider into plastic cups and handed one to each of us.

“You didn’t have to buy me a drink,” my daughter said. “And we don’t have to talk about plums.”

“It’s just nice to find companionship in these times. As you said, we are both here without our families.”

“Yes,” my daughter said. “Do you have any children?”

“I wasn’t blessed,” I said.

“Here’s to not being blessed,” she said, and raised her glass to me. She drank the cider, all of it, down in one swing. And then she ordered another, which I paid for, and then she said she wanted something more to drink. I was surprised. What, my god, have you not yet had enough? “It’s the last,” she said, “to celebrate our acquaintance on this perfect autumn day.”

And so I ordered again, and she took one more swig of cider. Then, at last, she stood up, this carnivorous tree-being I had perhaps dreamed forth into the world. She clambered to stand on the barrel that had once been her seat. She raised her arms into the air, her thin black dress whipping around her tattooed calves.

The whole place settled, hushed, even the voices of children. She was a spectacle, awesome and terrible. She raised her glass. To me. To me. Looked me in the eye. “Cheers,” she said, and spoke:

Out of the ash

I rise with my red hair

And I eat men like air.

And then I knew with horror that she was mine. Only mine.

And I split in half, just like an oak struck by lightning. And out of me tumbled my childhood dog, Anaïs Nin, my grandmother’s cookies, all the yarn I’d ever bought, the waves from the ferry, washing out Tootsie glasses, my ex-boyfriend, who chased my dog away, the girl with the wheelbarrow, the Trimet bus, and four perfect apples.

The next morning when I woke, my first impulse, beyond thought, was not to wish I had a child. Instead, the taste of unripe plums, cold and sour and bitter and hard, danced across my tongue.